The Best Tea in the World

Sri Lankan Tea Taster Milindha Morahela Shares Celebrated Ceylon Teas with the East Bay

By Anna Mindess | Photos by Clara Rice

Milindha Morahela has turned his lifetime of experience with Ceylon tea in Sri Lanka into an East Bay tea company and is looking forward to a future tea café.

“Tea is in my blood,” says Milindha Morahela.

An Emeryville resident, Morahela grew up in Sri Lanka on a huge tea estate managed by his stepfather. Now age 66, he’s looking back at a long career as a tea taster in his homeland while realizing a long-held dream of starting a tea company of his own.

Through Tea Friends, Morahela will sell Ceylon tea, “the best tea in the world,” as he calls it. Pure Ceylon Tea, as it is formally known (even since Sri Lanka won its independence from Britain in 1948) is always marked with the royal lion symbol. Morahela’s plans for 2026 also include opening a cozy tea house in Berkeley or Emeryville.

Mili (as Morahela likes to be called) was 21 when he faced a difficult decision. He had distinguished himself in college and then aced two high-level interviews: one to become a pilot with the Sri Lanka Air Force and the other to enter the tea field as a professional taster. “My family advised me to become a pilot, but my inner soul led me to become a tea taster.”

His grandparents, parents, and uncles on both sides had owned or managed tea estates, where they grew and processed tea. Morahela, who still owns his family’s 100-year-old estate, was well acquainted with the three-tier tea factories where the top floor was for withering the leaves, the middle for fermentation, and the ground floor for rolling, drying, grading, and packing.

Mili was 12 when his father passed away. His mother remarried Tissa Bandaranayake, another professional tea planter, who managed tea estates owned by the British. The boy developed a close relationship with his stepfather, now 93, whom he affectionately calls “uncle.” Bandaranayake advised Mili not to follow in his own footsteps as he foresaw that the tea estates would be managed differently by the new government than they had been by the British.

That’s how Morahela became the first in three generations to step up to the front of the tea industry: Instead of managing fields and a factory, he would become a tea taster and later a tea auctioneer. To train as a tea taster, he apprenticed for six months to a master at John Keells Holdings, a company that later grew to become one of the oldest and largest business conglomerates in Sri Lanka.

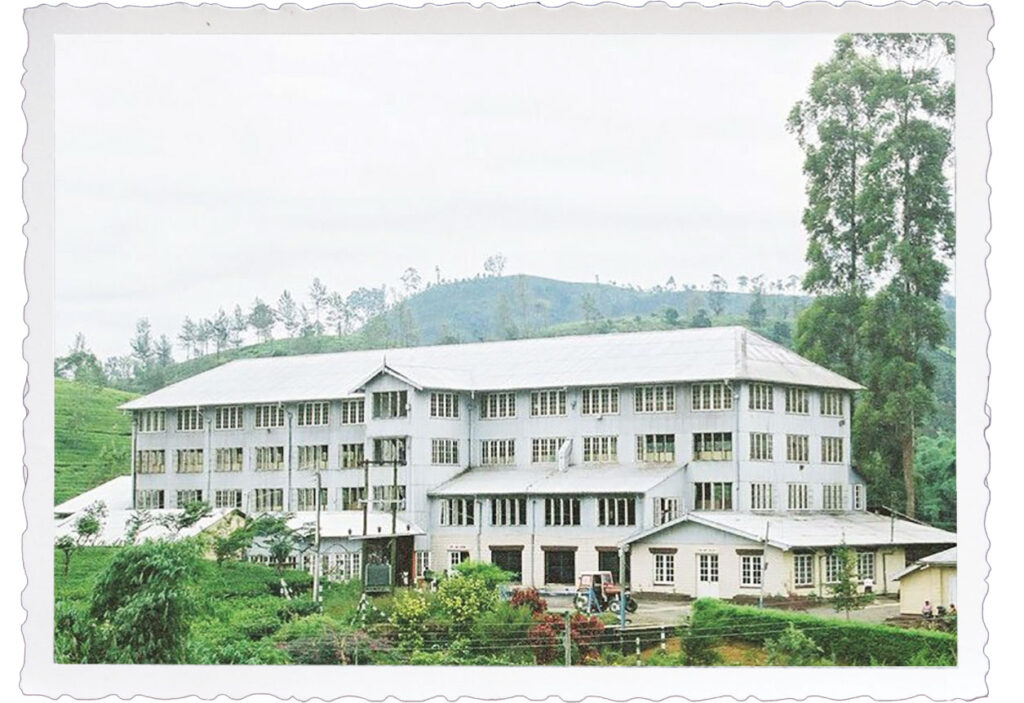

A typical high elevation tea estate. (courtesy: Gamini Wijesinghe)

Many tea growers handle their tea processing in factories on the estate so they can control tea quality through every stage of processing. (courtesy: Export Development Board)

Professional tea tasters in Sri Lanka use all of their senses to evaluate tea samples, often tasting hundreds of teas a day. (courtesy: Sri Lanka Tea Board)

Three Steps to Tasting Tea

“There are three steps to tasting a tea,” Morahela explains. “First you inspect the dry leaves; then you look at the tea infusion, or wet leaves; and finally you taste a small sip of the liquor, swishing it around in your mouth before spitting it out. There is a stenographer present who takes down notes for the tasters’ descriptions at each stage of the process.”

“There are three steps to tasting a tea,” Morahela explains. “First you inspect the dry leaves; then you look at the tea infusion, or wet leaves; and finally you taste a small sip of the liquor, swishing it around in your mouth before spitting it out. There is a stenographer present who takes down notes for the tasters’ descriptions at each stage of the process.”

In the typical tea tasting room, a long table holds a row of 200–300 white porcelain teacups with special lids that allow hot water to pass through the tea leaves to the cup below. During a single day, Morahela would typically taste 200–400 teas, depending on the season.

“A professional tea taster can pick up the tastes faster if they are not eating a lot of sweets or spices, drinking alcohol, or smoking,” Morahela cautions. “Those hide the intricacies of tasting the tea.”

Just like wine tasters, tea tasters employ a specific vocabulary to describe the look, smell, and flavor of the teas. For example, Morahela says, “You can describe the tea as bright or fruity or pungent or lively. Or if it is not good, we may call it wishy washy, as when the monsoon rains give it a flat taste.” Other negative terms are spicy, which can be caused when the tea is contaminated with spices. Burnt or bakey are used when the leaves are overfired in the dryer. But even teas bearing those negative descriptors may be sold to be blended with other tea leaves.

Professional tea tasters can predict a great deal about flavor even before they taste the tea. “When we observe the leaves,” says Morahela, “We already have a 50 percent idea of what it will taste like. Observing the infusion will tell you another 25 to 30 percent. Then tasting it is just the confirmation of the knowledge that you’ve gotten visually.”

Morahela also learned to identify the characteristic tastes of the three different elevations where tea is grown in Sri Lanka, from 2,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level. “High grown produces the finest tea because of the wind,” he explains. Wind takes the water off the tea leaf, while the quality remains intact. Some experts can even deduce what time of day the tea leaves were picked. “The best time to pick the bud and the first two leaves is in the morning,” says Morahela. “Tea leaves picked in the morning, called first flush, are the freshest because they have not been exposed to the harsh midday sun, which may make them withered and sunburned.”

In the Auctioneers’ Cyclone

After he had mastered the art of tea tasting, Morahela’s responsibilities broadened to include valuing the tea and eventually becoming one of the fast-talking auctioneers who sell huge quantities of tea at the twice-weekly Colombo Tea Auction, a synchronized and choreographed tradition that goes back to 1883 and handles 12–15 million pounds of tea per week. In Morahela’s day, the auctions still took place in an old-style British colonial wood-paneled room with 100–200 buyers present and English as the official language, as it had been since the auctions were established. It was a formal affair with the auctioneer and two assistants up on a riser and the potential buyers, all men in white shirts and black ties, in seats fanned around them. The sales proceeded in a speed-selling cyclone as the auctioneers were expected to sell eight lots a minute from their company’s catalogue. For each sale, they announced the lot number, estate name, grade, and starting price before accepting the first bid. The tap-tap of a small hammer signified when each sale closed.

After he had mastered the art of tea tasting, Morahela’s responsibilities broadened to include valuing the tea and eventually becoming one of the fast-talking auctioneers who sell huge quantities of tea at the twice-weekly Colombo Tea Auction, a synchronized and choreographed tradition that goes back to 1883 and handles 12–15 million pounds of tea per week. In Morahela’s day, the auctions still took place in an old-style British colonial wood-paneled room with 100–200 buyers present and English as the official language, as it had been since the auctions were established. It was a formal affair with the auctioneer and two assistants up on a riser and the potential buyers, all men in white shirts and black ties, in seats fanned around them. The sales proceeded in a speed-selling cyclone as the auctioneers were expected to sell eight lots a minute from their company’s catalogue. For each sale, they announced the lot number, estate name, grade, and starting price before accepting the first bid. The tap-tap of a small hammer signified when each sale closed.

Tea Friends

In 1990, after working for 10 years at John Keells, Morahela left the company and joined a friend in the textiles business. In 2006, a romance inspired him to move to the United States. His English was impeccable, but locals here had to tell him to slow down, since after 10 years of selling hundreds of tea lots for eight hours a day twice a week, Morahela still spoke English at a breakneck pace.

On relocating to the Bay Area, Morahela started his own printing and yoga apparel businesses, but as of October 2025, he has finally taken hold of his dream. With the launch of his own tea company in the East Bay, Morahela now has the chance to showcase the quality of Sri Lankan tea to the rest of the world. He’s named his company Tea Friends to honor the lifelong friendship between his stepfather, Tissa Bandaranayake, and Sam Rajiah, who recently passed away at the age of 94. The two had worked together in the tea industry for a combined total of 100 years.

Morahela’s new company will let him address unmet opportunities he observed in his earlier career with John Keells Holdings.

I found that my outlook on tea was much wider than the company’s. Their outlook was to get the tea from the manufacturer, auction it, and sell it. My idea was to market our Sri Lankan tea to the rest of the world. I was frustrated, because this is the best tea in the world, but it was not getting the price it deserved. I tried to advocate while I was there. Why do we have to go through this auctioning system? We can’t sell it directly? But it had to go through the Sri Lankan tea board. Only a small percentage was allowed to be sold directly. The British placed this system there so that they could buy the tea cheaply and blend it with other things and make a profit. This was the same British system that was still going on. I knew the back end of the tea industry. And I realized, oh my god, the amount of work, the labor, and the cost that is going to manufacture this tea that I am selling at the auction every week. It’s worth 10 times the amount it receives.

Tea Friends offers four single-origin teas: blended Earl Grey (flavored with bergamot orange peel); fine grain black tea in tea bags; unflavored orange Pekoe long leaf tea with a mellow, light liquor; and a handmade tea that Morahela’s maternal grandfather used to make when he was a child, which is unprocessed, sun dried, and hand rolled.

Morahela also sells tea sets, tea books, and cotton T-shirts and aprons with his logo of a teapot and the motto “drink • talk • love.” He hopes to soon be selling his teas in stores such as Whole Foods and Monterey Market and is looking forward to hosting tea lovers in his café next year. He plans a large space with several rooms, a menu of egg sandwiches and scones, and a selection of teas.

“The tea trade in Sri Lanka is called the ‘gentleman’s trade,’” he says. “And we pride ourselves on this, as ‘honesty and integrity’ and ‘promise given promise kept’ are the cornerstones of interaction with one another.” ♦

Anna Mindess is an award-winning journalist who writes on food, culture, and travel for numerous publications including the Washington Post, Atlas Obscura, and Berkeleyside. Follow her on Instagram @annamindess and find her stories at annamindess.contently.com.

Clara Rice is an East Bay–based commercial, editorial, and portrait photographer. Her work spans from restaurants to brand advertising, and she is always looking to meet new local faces. clararice.com